Tilman Walterfang - Seabed Explorations

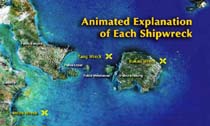

News

Tilman Walterfang - Seabed Explorations NZ Ltd.

The Belitung Shipwreck in its Historical Context (Complete)

NEW YORK, April 22, 2017 — In the first academic gathering in the United States to present a comprehensive review of the Belitung shipwreck, John Guy, Derek Heng, and Bryan Averbuch discuss various aspects of maritime trade routes during the Tang Dynasty period. The conversation was part of a symposium co-organized by Asia Society and the Tang Center for Early China at Columbia University and was moderated by Dora C.Y. Ching with welcome remarks by H.M. Agnes Hsu-Tang.

See the video: (2 hr., 20 min.) https://asiasociety.org/video/belitung-shipwreck-its-historical-context-complete

See the exhibition: "Astonishing" / "Full of lessons big and small" — The Wall Street Journal

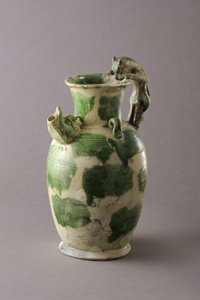

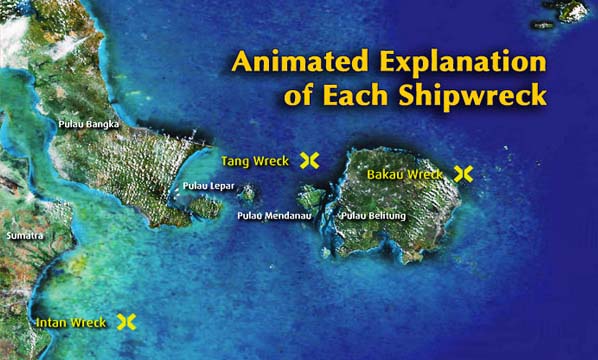

In 1998, Indonesian fishermen diving for sea cucumbers discovered a shipwreck off Belitung Island in the Java Sea. The ship was a West Asian vessel constructed from planks sewn together with rope — and its remarkable cargo originally included around 70,000 ceramics produced in China, as well as luxurious objects of gold and silver. The discovery of the shipwreck and its cargo confirmed what some previously had only suspected: overland routes were not the only frequently exploited trade connections between East and West in the ninth century. Whether the vessel sank because of a storm or other factors as it traversed the heart of the global trading network remains unknown. Bound for present-day Iran and Iraq, it is the earliest ship found in Southeast Asia thus far and provides proof of active maritime trade in the ninth century among China, Southeast Asia, and West Asia... Read more...

Secrets of the Sea: A Tang Shipwreck and Early Trade in Asia

US$32 million shipwreck treasure salvaged, conserved and displayed

Pieces from the Belitung Shipwreck exhibition are now displayed at the New York Asia Society Museum. This is the first time the treasure has travelled to America after a botched attempt to display it at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington D.C in 2011. Read more...

UNESCO AND THE BELITUNG SHIPWRECK:

THE NEED FOR A PERMISSIVE DEFINITION OF “COMMERCIAL EXPLOITATION”

By Patrick Coleman

George Washington University

I. INTRODUCTION

In 1998, fishermen diving for sea cucumbers off the coast of Belitung Island in Indonesia accidentally discovered the wreck of a ninth-century AD Arabian ship laden with cargo from Tang dynasty China.

Looting began almost immediately. The Indonesian government could not afford to protect or recover the shipwreck, so it granted a salvage permit to Seabed Explorations, a German company with experience in the region, in an effort to both preserve the artifacts and prevent them from being dispersed in a manner that would leave them unknown to the public and the academic community. Within two years of receiving the permit, Seabed recovered over sixty-three thousand artifacts, which it later sold as a complete collection to the government of Singapore for $32 million.

Singapore built a permanent museum installation for the shipwreck, and in conjunction with the Smithsonian Institution, organized a five-year traveling exhibition to allow people all over the world to see the artifacts. The recovery of the Belitung Shipwreck complied with Indonesian and arguably customary maritime law. Read more...

Interview with Tilman Walterfang

by Guy Scriven for The Economist UK

24. Februar 2013

1. What was your background before you became a maritime archaeologist?

I am not a maritime archaeologist but I employ archaeologists as projects require it. Professionally, I’m an engineer – a Master in mechanical engineering. Before I became involved with the Tang Treasure I managed a concrete products company in Germany.

More important is my cultural upbringing. My father was a sculptor and art historian and my mother a photographer and fine arts painter. My childhood entailed frequent visits to museums, archaeological sites, cathedrals and art auctions all over Europe. I would watch my father producing and restoring works of art in his workshop and we were surrounded by all kinds of artifacts and antiquities.

So my background is a mix of cultural appreciation and the skills of technical and strategic management. These attributes helped when I was first confronted with the challenge of managing the discoveries of some Indonesian fisherman.

2. What drew you into the industry?

My Indonesian employees and Indonesian brother-in-law told me about some maritime discoveries in Indonesia in 1993. I went to Indonesia two years later for a diving trip, and confirmed their reports. I brought back some samples from a 13th century and 15th century shipwreck and spoke to museum directors and universities to garner interest. I was warned that salvaging shipwrecks in Indonesia was too difficult and one professor told me that there was no funding to protect these sites from looters and he recommended to look at it from a commercial angle. It seemed like a hopeless task and this triggered my interest to investigate further.

3. How has the UNESCO 2001 UCH convention changed your work?

The Convention changed our work in a very positive way. The UNESCO awareness campaign improved my understanding of the difficulties nations face in managing their underwater cultural heritage. It’s fundamentally good to work within best-practice guidelines.

However, we must be realistic about UN conventions. Only two states along the maritime silk route between the Arabian Gulf and China ratified the UCH Convention: Iran and Cambodia. All other countries with access to the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific did not ratify the convention. That extends to the US, UK and many other countries, involving hundreds of thousands of unexplored shipwreck sites. These countries raised concerns as to the compatibility of the Convention with the international law of the sea and their respective national legislations. During our Tang shipwreck recovery in 1998 the Convention did not exist but after it was published in 2001 we found that we’d followed most of the rules and guidelines listed in the Annex of the convention. We did not irretrievably disburse the find through an auction for commercial gain but kept it together; we thoroughly preserved all recovered artifacts, the hull and organic materials were properly recorded, we commissioned scholars from various countries to research the find and we provided comprehensive publications of the research. Exhibitions are held for the enjoyment of all and the find is kept together and accessible for research and study under the stewardship of Singapore.

4. Do you think the laws should be changed or altered?

Laws are for the individual nations to enact, and even ratifying a UN convention such as the UCH doesn’t guarantee the outcomes we would all prefer. The fact is that there is ongoing destruction and looting of some very interesting archaeological wreck sites. We’ve reported some we know about to the authorities, hoping for in situ protection as recommended by the Convention – even then, the sites were looted after two years. But ultimately, each nation has to pass and enforce its own laws regarding maritime cultural heritage. Some countries are making efforts to harmonise their national legislation with the UCH Convention. But it would be more helpful if it worked the other way, and the convention was harmonised with national legislation. Logically, valuable shipwrecks are more exposed to looting than other shipwrecks, therefore nations need support to save and preserve them.

5. How did it feel to discover the Belitung wreck?

The Belitung shipwreck was discovered by fisherman who were employed by us. Thus I did not personally discover the Belitung wreck, but I can say that the excitement was overshadowed by the extremely difficult circumstances in the field, our lack of preparation for the scale of the work, and a dangerously volatile situation.

6. What was the most exciting artifact recovered from the Belitung?

For me all artifacts have the same fascination. Every piece tells a story.

7. How do you respond to accusations that the Belitung salvage did not meet archaeological standards?

Most of our critics have made their careers as academics and they don’t operate under the practical and political pressure we were presented with. I use this metaphor: the first paramedic to arrive in an emergency applies a standard of medical care that the surgeon in her operating theatre will say does not meet ‘medical standards’. But the first paramedic saves the person’s life. The first season on the Belitung wreck was a first aid rescue operation. It was a triage. The team of scientists on site had the qualifications to meet archaeological standards, however the immense pressure by the government to finish the operation within only a few weeks and the volatile situation in the country [the fall of the Suharto regime] compelled the scientists to make compromises. Great sacrifices and risks were involved for the team and I stand by them and their decisions.

In the second season we were better prepared and when we reached a settlement with the government we were able to employ Dr Mike Flecker to record the site and the hull of the ship without too much pressure. Unfortunately the site was heavily looted and destroyed during the monsoon season despite the permanent presence of navy personnel. Nothing about these ventures is simple.

8. Are you working on any other salvage projects?

No. Our focus right now is to identify and discover shipwrecks to be added to our portfolio of opportunities.

9. Is it difficult to find investors for such a high-risk, high-reward business?

It is not easy, but you learn lessons from past mistakes and through thorough due diligence and project diversification, the risks can be significantly reduced. During past recovery operations and the process of conservation, research and utilisation, our company was confronted with a wide range of challenges to overcome. We combined this experience with analysis of the performance of other operating companies in Asia and worldwide, to create a business model with the potential for high profitability. This business model has been translated through field experience and exhaustive diligence into a cost structure. We’ve spent several years in the planning process, engaging experts in every area of operation.

Interview with Tilman Walterfang about the Belitung Shipwreck

for World Archaeology

January 6, 2012

<>1. In archaeological terms, why is the Belitung shipwreck so important?

Tilman Walterfang:

"Apart from its contribution to our understanding of a myriad of issues

related to the Tang Dynasty era – among them ancient trade

networks, glazing techniques, mass production, craftsmanship,

international communication with the exchange of ideas and religious

beliefs along the ancient maritime silk-route – it also seems

to teach us nowadays something about both the potential of Underwater

Cultural Heritage and the threats to it. The Belitung wreck is also a

wake-up call to update outmoded positions which were taken in a time

without the internet and with little knowledge about the real threats

to UCH and less developed technical capacities to discover and explore

such sites. This extends to the positions of government, the private

sector as well as archaeologists, museums and participants in

international art trade.

Tilman Walterfang:

"Apart from its contribution to our understanding of a myriad of issues

related to the Tang Dynasty era – among them ancient trade

networks, glazing techniques, mass production, craftsmanship,

international communication with the exchange of ideas and religious

beliefs along the ancient maritime silk-route – it also seems

to teach us nowadays something about both the potential of Underwater

Cultural Heritage and the threats to it. The Belitung wreck is also a

wake-up call to update outmoded positions which were taken in a time

without the internet and with little knowledge about the real threats

to UCH and less developed technical capacities to discover and explore

such sites. This extends to the positions of government, the private

sector as well as archaeologists, museums and participants in

international art trade.

Another important aspect is that our concept of evaluating a shipwreck for its potential to develop strategic capital, rather than seeing its value only in the general terms of artefact trade and auction prices, has been proven as a viable option to prevent the untraceable disbursement of artefacts in the art market. The downstream benefits of such strategic value are reflected in the Jewel of Muscat project, which provides a platform for cultural diplomacy between nations to rekindle old relations, with the discovery of shared cultural roots and values based on a peaceful and prosperous trade history."

2. There was clearly much effort placed on the documentation and restoration of items retrieved from the Belitung wreck. Do you think there has been a degree of academic snobbery in how the recovery of the Belitung has been conducted? (I wanted to know if you felt that "armchair academics" had been negative about the salvaging of the wreck without fully understanding the problems that were faced in the process (i.e. it would have been lost as a collection if the salvage process was not undertaken).

Tilman Walterfang: "It is quite obvious that the critics of our work have sufficient acumen to fully understand the problems that we faced during the operational phase. Thus I would rather distinguish between academics who are striving with integrity to uphold ethical values to protect precious sources of knowledge about human history, and academics who are lacking in integrity and using false and misleading information. The deceitful spin of the latter group may serve their short-term goals, but I do not see them prevailing in the long run."

3. Some experts have voiced strong concerns about commercial involvement in shipwreck and cargo recoveries, claiming they compromise scientific standards. Give the very real threats to the Belitung site from looting, how unrealistic are these concerns? Was a full scientific excavation ever really possible here?

Tilman Walterfang: "Google was incorporated three weeks after we began the excavation process in 1998. Hence there was no easy access to any information which could have provided guidance in how to deal with the situation. The UNESCO Convention for the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage did not exist and the ICOMOS Charter was only known to the subscribers of professional journals in the museums community. The Indonesian government did not know anything about the concerns of some experts, and solely commercial considerations were the driving force behind the decisions of the National Committee which, with its representatives of 19 departments, was in charge of managing underwater archaeological affairs.

The pace of the excavation had nothing to do with the fact that our operations were privately funded. Please note that hiring an underwater archaeologist for one month costs no more than what we pay one of our lawyers for five hours’ work. With pleasure we would have financed a team of archaeologists to excavate the location off this beautiful tropical island for years if the circumstances had allowed it.

A full scientific excavation would have required as a first step a thoroughly drafted project design. With no time at all to prepare the operation, our team was totally unprepared to face this challenge and every little step in the process had to be improvised. The threat of imminent looting if we were to turn our backs on the wreck site for just a few hours was merely one of the detrimental factors which played a role in the decision-making processes. To mention only a few more:

- The fall of president Soeharto’s corrupt military dictatorship in 1998 left Indonesia in an extremely volatile power vacuum

- Travel warnings to Indonesia were in place and governments urged their citizens to leave the country

- Atrocities were reported on a daily basis from various centres of conflict across Indonesia in Papua Province, Aceh, Ambon, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, and East Timor

- In the beginning we were ordered to immediately recover the artefacts within two weeks’ time. After six weeks of operation we received another deadline to finish it within two weeks

- Safety concerns for the artefacts and the team were the main reason for the rush. Competing interests between departments and influential individuals were another reason

- Only after the exportation of the cargo, when we gained full control over the project, were we able to apply appropriate measures of documentation and preservation

- The scientists on site did the best they could and took great personal risks by joining the team

- In 1998 underwater archaeology was still in its infancy and we had no chance to find within days experienced underwater archaeologists who would have jumped on the next flight without second thoughts.

Considering the abovementioned examples of the countless difficulties we faced during the operation, there was absolutely no possibility at all of carrying out a thorough long-term excavation."

4. In an ideal world, long term excavation of maritime sites could be conducted in a safe and secure environment. Given the real threats of looters today, do you think placing too much emphasis on scientific survey and recording is damaging to the recovery of threatened underwater discoveries?

Tilman Walterfang: "Protecting Underwater Cultural Heritage is a complex challenge. UNESCO with all its resources is not even able to offer sufficient assistance to nation states with rich Underwater Cultural Heritage in accessible shallow waters to take initial steps in the management process of wreck sites.

In countries where the police and navy do not participate in lucrative looting and black-market activities, it is definitely easier to protect discovered wreck sites with their help. If we had taken the same position as the individuals and institutions which oppose any kind of commercial involvement, the Belitung wreck would have never been known to mankind and all the information would have been lost forever.

Thus, to answer your question succinctly, if placing too much emphasis on scientific survey and recording would be damaging to the recovery of threatened underwater discoveries, then solutions have to be developed on a case-by-case basis to prevent this from happening."

5. Are you disappointed by the Smithsonian’s decision not to host the Shipwrecked exhibition?

Tilman Walterfang: "I am not disappointed about this decision. Rather, I am surprised and feel sorry for the American people for being deprived of their right to enjoy the exhibition of this magnificent collection: even more so considering that the American people themselves are financing those who believe they have the right to spoon-feed the public.

Everything that happens during the lifecycle of an artefact, beginning with gathering of materials to produce an artefact until its display centuries later – is part of the history of the objects. No scientist with honest intentions should have a problem accepting the history of an archaeological item."

6. What is your reaction to the Smithsonian’s recommendation to re-excavate the Belitung site?

Tilman Walterfang: "I wish them good luck with it. I offered to the Indonesian government to finance this option in early 2000 and in 2003 under the condition of making it a purely non-profit operation just for research purposes. I proposed to invite research institutions from all over the world to join the project. This was rejected, and one reason was that it would have violated Indonesian law if the newly recovered artefacts were not to have been auctioned off. An auction and disbursement in the art market was never acceptable for me."

7. Do you think there needs to be a change in attitudes towards the involvement of commercial companies in the salvaging of shipwrecks and their cargo? How can the general state of maritime archaeology be improved by closer links between academia and commerce?

Tilman Walterfang: "The experts who categorically maintain their position that they have to be financed by taxpayers only, will sooner or later be compelled to reconsider the wisdom of their position. To uphold core values of a scientific discipline protects against the introduction of damaging compromising practices, and it is definitely worth standing for such values. However, it seems ridiculous to believe that modern developments in business ethics, politics and technical capabilities will not leave their mark on the management of underwater archaeology. Why should "doing well by doing good" not work here if the introduction of this concept shows so many promising developments across almost all industries? The simple solution is to tie commercial aspects to quality benchmarks in all associated disciplines. If medical practitioners are able to uphold high ethical standards while working commercially, why should archaeologists not be able to maintain high professional standards in a commercial operation?"

Articles

Editorial: Tang Treasures, Monsoon Winds and a Storm in a Teacup

"There lived in the city of Baghdad, during the reign of the Commander of the Faithful, Harun al-Rashid, a man named Sindbád the Hammá… for I was a merchant and a man of money and substance and had a ship of my own, laden with great stores of goods and merchandise; but it foundered at sea and all were drowned except me who saved myself on a piece of plank which Allah vouch safed to me of His favour" (One Thousand Nights and One Nights).

Storm in a Teacup

The adventures of Aladdin

and Ali Baba and the Fourty Thieves in One Thousand Nights and One

Nights are amongst our most cherished childhood stories, but what if

they weren’t entirely make believe? From the improbable

setting of the bottom of Indonesia’s Java Sea has risen

21st-century archaeological DNA that puts the oceanic adventures of

Sinbad the Sailor across Africa and Asia in a real world historical

context. The wreck of the first Arab dhow discovered in Southeast Asian

waters has produced clear evidence for direct trade between the Arab

world, the western Indian Ocean and China during the latter part of the

first millennium. Read more...

The adventures of Aladdin

and Ali Baba and the Fourty Thieves in One Thousand Nights and One

Nights are amongst our most cherished childhood stories, but what if

they weren’t entirely make believe? From the improbable

setting of the bottom of Indonesia’s Java Sea has risen

21st-century archaeological DNA that puts the oceanic adventures of

Sinbad the Sailor across Africa and Asia in a real world historical

context. The wreck of the first Arab dhow discovered in Southeast Asian

waters has produced clear evidence for direct trade between the Arab

world, the western Indian Ocean and China during the latter part of the

first millennium. Read more...

The Belitung Tea Bowl in the Eyes of an American Scholar

by Professor Victor H. Mair from the University of Pennsylvania

The International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS)

Newsletter: 42

"The educational and historical value of he

collection is simply enormous, and those who have called for the

cancellation of the exhibition are, in effect and in fact, denying

access to the wealth of information embodied in the Belitung shipwreck.

As a remarkable case in point, the Belitung chazhanzi (“tea

bowl”) constitutes the single most important and solid datum

for the history of tea in the Tang period and arguably for the history

of tea in general. So vital is this unique object from the Belitung

shipwreck that it became the thematic logo for our entire book (The

True History of Tea, written by myself and Erling Hoh), yet it is only

one out of roughly 60,000 artefacts preserved and conserved by the

excavators. I shudder to think that, were it not for their swift, yet

rigorous and careful actions, this inestimably precious artefact might

well have been lost forever to the depredations of callous looting and

the vagaries of ocean currents. When we multiply the significance of

this one bowl several thousand-fold, we can get a sense of the

diminution that would have resulted if the Belitung shipwreck had not

been rescued by the decisive actions of the excavators. Consequently,

it should be obvious that the detriment to human understanding of the

past would be of incalculably tragic proportions."

"The educational and historical value of he

collection is simply enormous, and those who have called for the

cancellation of the exhibition are, in effect and in fact, denying

access to the wealth of information embodied in the Belitung shipwreck.

As a remarkable case in point, the Belitung chazhanzi (“tea

bowl”) constitutes the single most important and solid datum

for the history of tea in the Tang period and arguably for the history

of tea in general. So vital is this unique object from the Belitung

shipwreck that it became the thematic logo for our entire book (The

True History of Tea, written by myself and Erling Hoh), yet it is only

one out of roughly 60,000 artefacts preserved and conserved by the

excavators. I shudder to think that, were it not for their swift, yet

rigorous and careful actions, this inestimably precious artefact might

well have been lost forever to the depredations of callous looting and

the vagaries of ocean currents. When we multiply the significance of

this one bowl several thousand-fold, we can get a sense of the

diminution that would have resulted if the Belitung shipwreck had not

been rescued by the decisive actions of the excavators. Consequently,

it should be obvious that the detriment to human understanding of the

past would be of incalculably tragic proportions."

by Lu Caixa, a researcher at the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore

[..] The excavation of the Belitung has been acknowledged as an admirable example of what can be achieved under difficult conditions in Southeast Asia. What distinguished the company that carried out the Belitung project from some other commercial operators is that the ship structure itself was properly recorded, the cargo was kept together rather than dispersed, and the finds were well conserved, studied, catalogued, and published. A global exhibition was created and a reconstructed dhow based on information gleaned from the excavation sailed across the Indian Ocean. Few non-commercial excavations have achieved comparable results with a project of this scale and complexity. It is difficult to imagine how this particular project could have been financed or organized without commercial involvement. [..]

[..]Seabed Explorations founder Tilman Walterfang defended the company’s work on the Belitung, arguing that immense pressure to save the shipwreck in the face of heavy looting and a volatile political climate dictated the pace and manner in which the artefacts were retrieved. When first approached by the Indonesian government for help, commercial benefit was the last thing on his mind; it became an emergency operation to save as much of the cargo as possible before it fell prey to looters. [..] Read more...

Academe's exhibition of parochialism

Andy Ho

The Straits Times

Publication Date : 23-12-2011

Under pressure, the Smithsonian has nixed its plan to host Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures And Monsoon Winds.

Based in Washington, the renowned museum co-curated that exhibition in Singapore this year. The display, which was to tour the world next year, consisted of 400 Tang-era ceramic and gold artefacts retrieved from an Arab dhow that sunk off Belitung island some 1,100 years ago.

Soon after fishermen first located it in 1998, the Indonesian government authorised a German commercial salvage operation to recover the sunken cargo. This was later sold to Sentosa Leisure Group in 2005 for an estimated US$32 million.

Partisans argue that because a commercial salvor was involved, the spirit of the Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) had been violated. That treaty urges that all sunken relics be preserved in situ. It also forbids virtually all commercial salvage work.

As such, proceeding with Shipwrecked would endorse the unethical practices of treasure hunters, they aver. However, that treaty, which entered into force in 2009, has only 40 signatory nations, none of them the large markets for UCH such as the United States and Europe - nor Singapore and Indonesia. So it is a stretch to claim that world opinion finds Shipwrecked not kosher in some sense. Read more...

Exploring the Future of Undersea Evacuation

by Sarah Mich:

Boston Globe

May 10, 2011 at 7:39 pm

Halfway around the world from the beaches of California, a ship that carried the secret to an ancient trade route rests quietly on the ocean floor. The vessel is an Arab dhow, not more than 20 meters long, crafted from planks tied together with pieces of stout twine. When it sank off the coast of Indonesia 12 centuries ago, its hull filled with Chinese ceramics, it was bound for modern-day Iraq. Read more...

Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and

Monsoon Winds

Shipwrecked: Tang Treasures and

Monsoon Winds

Media Backgrounder: Discovery, Recovery, Conservation and Exhibition of the Belitung Cargo

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

March 16, 2011

In 1998, fishermen diving for sea cucumbers off the coast of Belitung, a small island in the Java Sea, discovered a mysterious mound rising above the flat seabed. It was found to consist of an ancient shipwreck with an immense cargo of Chinese ceramics. When the ship was recognized as an Arab dhow, scholars realized that this was the first intact proof of a maritime trade route between West Asia (probably the Abbasid capital of Baghdad) and China in the ninth-century CE.

- The objects were discovered in 1998 by local fishermen in shallow waters off the coast of Belitung Island, Indonesia.

- Neither local nor national Indonesian authorities had the resources or expertise necessary to mount a full-scale archaeological excavation and the newly discovered shipwreck was immediately vulnerable to looting and damage.

- At the same time, due to political turmoil caused by the fall of the 32-year-old Suharto regime in May 1998, it proved difficult for the Indonesian government to guarantee the security and safety of the shipwreck location, risking the complete destruction of an archaeological site of substantial promise. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - Introduction

Issues Raised by the Belitung Shipwreck

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

Discovered in shallow water near inhabited shores in 1998, the Belitung shipwreck was immediately vulnerable to looting and accidental destruction due to fishing activity. Soon after the ship was found, Indonesian authorities granted a license to a salvage company, which employed archaeologists to record details of the site, the ship, and its contents. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - Why Exhibit this Material?

A Message from Julian Raby (Director of the Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Smithsonian Institution)

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

Several factors solidified my decision to co-organize a world tour of objects from the Belitung shipwreck. First, the ship's salvage was legal under Indonesian law. Beyond that, special care was eventually given to the recovery, with an archaeologist recording details of the boat and site, and retrieving organic materials—including samples from the hull, to which some salvagers pay scant attention. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - The Belitung Excavation

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

Twelve centuries ago, a merchant ship—an Arab dhow—foundered on a reef just off the coast of Belitung, a small island in the Java Sea. The cargo was a remarkable assemblage of lead ingots, bronze mirrors, spice-filled jars, intricately worked vessels of silver and gold, and approximately 60,000 glazed bowls, ewers, and other ceramics. The ship remained buried at sea for more than a millennium, its contents protected from erosion by their packing and the conditions of the silty sea floor. It wasn't until 1998 that fishermen diving for sea cucumbers discovered the wreck, lying in shallow waters less than three kilometers offshore. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - The Institutional Framework

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

While divers have been exploring shipwrecks for centuries, the scientific excavation of underwater artifacts is a relatively new field, having only come of age in the second half of the twentieth century. Today, a number of national and international organizations act in an advisory capacity for issues surrounding underwater cultural heritage management. The groups listed below serve as clearinghouses for information on newly discovered shipwrecks, ongoing excavations, and new research. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - To Read More

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

As shipwrecks are inaccessible to most, publication of new research is the primary avenue for advancing the field of underwater archaeological heritage. There are a number of journals specializing in this subject, the best known of which is the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology. Research institutes dedicated to marine archaeology and organizations that sponsor related research often post field reports on ongoing excavations and other new information on their websites. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - Training and Research

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

The field of underwater archaeology involves the work of archaeologists and specialists in related fields, such as conservation, conservation science, and history. Underwater archaeologists attend graduate programs generally housed within archaeology or marine studies programs at universities in Australia, North America, and Europe. Shorter-term workshops in underwater archaeology take place regularly in Thailand, sponsored jointly by UNESCO and local organizations. Discussions are underway about establishing training programs in China as well. Read more...

Underwater Cultural Heritage - Maritime Museums around the World

Freer / Sackler the Smithsonian's Museum of Asian Arts

Human interaction with the sea has affected politics, economics, warfare, technology, trade, and culture since the beginning of our history. There are hundreds of museums scattered across the globe (the majority in Europe, North America, and Australia) that document and display some aspect of this long relationship. These institutions include historic buildings, such as lighthouses, docks, and fishermen’s cottages; museums of naval history; reclaimed vessels arranged for public tours; and many more. Read more...

Tang Treasure and Monsoon Winds

George Yeo, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Singapore

Foreword

|

|

George

Yeo, Minister for Foreign Affairs, Singapore |

The ninth-century Arab dhow that carried the Tang Shipwreck Treasure and sank some 400 miles south of Singapore was part of an earlier era of globalization. It was the age of the Tang, China’s greatest dynasty, and the height of the Abbasid Empire. The cities of Chang’an and Baghdad were linked by commerce transported via both overland and maritime silk routes. In the previous century, at the battle of Talas, an eastward-moving Abbasid army had defeated a Tang army that crossed the Tian Shan mountain range in Central Asia.

According to one account, the Abbasids captured Chinese papermakers and learned how to mass-produce paper. That technology, which the Chinese had kept secret for centuries, quickly moved westward, transforming the Islamic world and, much later, Europe. After Talas, no Chinese army would cross the Tian Shan again. It was enough to trade. Trade flowed over land and sea, linking diverse parts of Asia. As ships could carry a much greater load than camels could, the maritime route from East Asia through Southeast Asia to South and West Asia became more important, with the Gulf serving as an important hub.

Buddhism and Islam were the portable religions of the time. In Southeast Asia, Buddhist Srivijaya held sway. In South Asia, the great Buddhist university, Nalanda, received monks who traveled through Central and Southeast Asia. The encounter between Buddhism and Islam was largely peaceful, a relationship that continues to this day. Indeed, the Tang Shipwreck Treasure collection was found with pieces bearing Buddhist and Islamic motifs sitting side by side. We hear echoes of that world in this century. In a new age of globalization, different parts of the world are connected once again by trade. By researching the voyage of the collection, its content, and the global economy of that period, we can learn lessons that apply today. Diversity may be a reason for conflict, but it also can be a source of learning and creativity. In celebrating that glorious past, we can draw inspiration for the future. Read more...

Foreword

Aw Kah Peng, Chief Executive, Singapore Tourism Board

|

|

From left to right: Alvin Chia, Andreas Rettel, Minister George Yeo |

Cities represent the diversity of lives within shared spaces. They are special because they contain the collective experiences of many communities over centuries. Since ancient times, cities have been the sites where talent congregates and creation takes place. They have inspired great inventions, from scientific discoveries to innovations in pottery, art, and craftsmanship. We understand this because Singapore is one such place. That is also why the artifacts from the Tang Shipwreck Treasure excite so many of us in Singapore. They not only shed light on our personal and national histories, they are also a window into the past of many great cities. We were deeply impressed when we learned how these invaluable artifacts ended up in our part of the world and about the historical significance associated with being near our waters.

Truly, this collection helps tell the story of how Singapore grew from a fishing village into the modern metropolis it is today. It also underscores how the city benefited from its strategic location in the global trade network and the cultural exchanges that arose through that trade. The Singapore Tourism Board (STB) is honored to play a role in showcasing the Tang Shipwreck Treasure: Singapore’s Maritime Collection. By presenting the collection first in Singapore and subsequently to a global audience, we hope to give audiences a di erent and deeper perspective of our island-nation. We believe the artifacts will help draw the link between the city-state that exists today and the rich historical narrative of the past.

STB would like to put on record our deepest appreciation to the Estate of Tan Sri Khoo Teck Puat for its generous contribution toward the acquisition of the artifacts. Mr. Khoo Teck Puat was one of Singapore’s best-known businessmen and philanthropists. This world tour also would not have been possible without our esteemed partners—the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery and the National Heritage Board, Singapore. It is hard for words to do justice to the Tang Shipwreck Treasure: Singapore’s Maritime Collection. The best way to fully appreciate the collection is to see the artifacts firsthand and be taken on a magical historical journey. We invite you to enjoy the exhibition. Read more...

Another ancient sailing ship to set forth

|

|

Jewel of Muscat in her first sea trials |

When 15 Omani sailors set sail from the port of Muscat next month, it will mark the beginning of yet another attempt to recreate the journeys of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of years ago.

In other examples of what seems to be becoming a world-wide trend, the Phoenicia, an ancient replica of an Egyptian sailing vessel, is currently circumnavigating Africa, and last year a Chinese vessel, the Princess Tai Ping was tragically split in two when just one day from completing a double trans-Pacific crossing when it was hit head-on by a cargo ship.

In the new effort, the ninth century wooden square-rigged

sailing ship will be heading for Singapore. It has been modelled on the

famous Tang Treasure ship that sank in the Indian Ocean while laden

with gold and other precious items belonging to the old Chinese Tang

dynasty.

Read more...

Investing in Culture: Underwater

Cultural Heritage and

International Investment Law

Valentina Sara Vadi

ABSTRACT

Underwater cultural heritage (UCH), which includes evidence of past cultures preserved in shipwrecks, enables the relevant epistemic communities to open a window to the unknown past and enrich their understanding of history. Recent technologies have allowed the recovery of more and more shipwrecks by private actors who often retrieve materials from shipwrecks to sell them. Not all salvors conduct proper scientific inquiry, conserve artefacts, and publish the results of the research; more often, much of the salvaged material is sold and its cultural capital dispersed. Because states rarely have adequate funds to recover ancient shipwrecks and manage this material, however, commercial actors seem to be necessary components of every regulatory framework governing UCH. In this context, this Article aims to reconcile private interests with the public interest in cultural heritage protection. Such reconciliation requires that international law be reinterpreted and reshaped in order to better protect and preserve UCH and that preservation of cultural heritage be recognized as a key component of economic, social, and cultural development. […]

Read more…New York Times

Ancient Arab Shipwreck Yields Secrets of Ninth-Century Trade

By SONIA KOLESNIKOV-JESSOP

Published: March 7, 2011

SINGAPORE — For more than a decade, archaeologists and historians have been studying the contents of a ninth-century Arab dhow that was discovered in 1998 off Indonesia’s Belitung Island. The sea-cucumber divers who found the wreck had no idea it eventually would be considered one of the most important maritime discoveries of the late 20th century. […]

Read more…

(C) 1998-2014 Copyright Tilman Walterfang - All rights reserved.